|

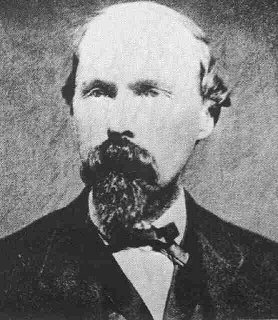

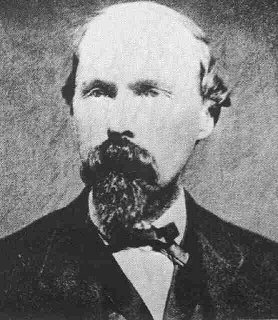

Library of Congress Photograph |

Dr. Samuel Alexander Mudd was born on December 20, 1833, on a large plantation in Charles County, Maryland. He was the son of Henry Lowe Mudd and his wife, Sarah Ann Reeves. As a youngster, Sam enjoyed swimming, fishing, hunting, and weekend trips with his dad. He attended public schools for two years, and Miss Peterson, a governess hired by his father, also tutored him. At age 14 he entered St. John's College in Frederick, Maryland. He stayed for two years. He then attended Georgetown College in Washington, D.C. In 1854 Mudd transferred to the University of Maryland in Baltimore and studied medicine and surgery. He graduated from that institution in 1856.

After graduation Dr. Mudd returned home and began life as a practicing physician and farmer. On November 26, 1857, he married Sarah Frances Dyer, his childhood sweetheart. The Mudds' first child, Andrew, was born in November of 1858. By 1859 the Mudds had a farm of their own. It was located about five miles north of Bryantown, Maryland, and 30 miles south of Washington, D.C. In 1860 the Mudds' second child, Lillian Augusta, was born. Two more sons were born in 1862 and 1864. During the Civil War, Dr. Mudd was a Confederate sympathizer and member of the Confederate underground.

On Sunday, November 13, 1864, John Wilkes Booth first met Dr. Mudd at St. Mary's Church near Bryantown, Maryland. Evidence indicates a second meeting of the two men took place c. December 18 at the Bryantown Tavern. Then, on December 23, the two men met yet again in front of Booth's hotel (the National Hotel) in Washington, D.C. Booth wanted Dr. Mudd to introduce him to the Confederate courier, John Surratt. Walking along 7th Street, the men came upon none other than Louis Weichmann and John Surratt! Booth invited all three men up to his hotel room for a drink. Depending on one's point of view, the discussion and events at this "meeting" were either totally innocent or "suspicious."

|

|

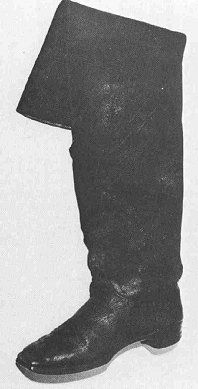

After he shot Lincoln, Booth broke his left leg in his leap to the stage at Ford's Theatre. Needing a doctor's assistance, he and David Herold arrived at Dr. Mudd's (about 30 miles from Washington) at approximately 4:00 A.M. on April 15, 1865. Dr. Mudd set, splinted, and bandaged the broken leg. (The National Park Service photograph to the left shows Booth's boot which Dr. Mudd removed when he treated the leg.) Although he had met Booth on at least three prior occasions, Dr. Mudd said he did not recognize his patient. He said the two used the names "Tyson" and "Henston."

With Booth still in his home Mudd made a trip to Bryantown to do some errands for his wife. While in Bryantown he first heard about the assassination.

Booth and Herold stayed at the Mudd residence until Saturday afternoon (roughly a 12-hour stay). Dr. Mudd asked his handyman, John Best, to make a pair of rough crutches for Booth. Dr. Mudd was paid $25 for his services. Booth and Herold left in the direction of Zekiah Swamp.

Within days Dr. Mudd was under arrest by the United States Government. He was charged with conspiracy and with harboring Booth and Herold during their escape. He went on trial along with Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, Mary Surratt, David Herold, Edman 'Ned' Spangler, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O'Laughlen. In court witnesses described Dr. Mudd as the most attentive of the accused. He was dressed in a black suit with a clean white shirt. Testimony against the doctor at the trial included his harsh treatment of some of his slaves. He shot one male slave (who survived). New information regarding Dr. Mudd surfaced in 1977. A previously unknown statement by conspirator George Atzerodt indicated that John Wilkes Booth had sent liquor and provisions to Dr. Mudd's home two weeks prior to the assassination. Like the other defendants, Dr. Mudd was found guilty. His sentence: life imprisonment. He missed the death penalty by one vote.

|

|

Dr. Mudd was imprisoned at Ft. Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas about 70 miles from Key West. (The photo is from "Lincoln's Assassins: A Complete Account of Their Capture, Trial, and Punishment" by Roy Z Chamlee, Jr.) Dr. Mudd was allowed to stay in mail contact with his wife. Mrs. Mudd also wrote letters to President Andrew Johnson seeking her husband's release. An attempted escape failed on September 25, 1865. In February of 1867 Dr. Mudd was assigned to the prison's carpentry shop. In the summer of 1867, yellow fever broke out on the island. After the fort's physician died on September 7, Dr. Mudd took a leadership role in aiding the sick. Dr. Mudd, himself, came down with the disease but recovered. Michael O'Laughlen was one of those who passed away due to the epidemic. Because of his outstanding efforts, all noncommissioned officers and soldiers on the island signed a petition to the government in support of Dr. Mudd. |

|

|

In 2006 my good friend, Jim Dohren, took the photo to the right. It shows the view looking out of Dr. Mudd's cell into the interior of Ft. Jefferson. There were no bars on the cell as there was no place to escape. |

|

|

In 2014 my good friend, Eva Lennartz, took the photo to the right. It shows the entrance to Ft. Jefferson. |

|

|

Early in 1869 a courier from the United States Government knocked on the front door of the Mudd farm. When Mrs. Mudd answered, the man handed her an envelope and said, "From the President of the United States. Please sign this receipt to certify that I have delivered it to you. If you have a reply, I shall return it for you." Mrs. Mudd opened the envelope and found a letter written on White House stationery. It read:

Dear Mrs. Mudd:

As promised, I have drawn up a pardon for your husband, Dr. Samuel A. Mudd. Please come to my office at your earliest convenience. I wish to sign it in your presence and give it to you personally.

Sincerely,

ANDREW JOHNSON

President of the United States of America

|

|

Mrs. Mudd went to the White House the next morning. There the president signed and delivered to her the papers for the release of her husband. The date of the pardon was February 8, 1869.

Dr. Mudd was released from Ft. Jefferson on March 8 and arrived home on March 20. He had served somewhat less than four years in prison. He partially regained his medical practice and lived a quiet life on the farm.

Dr. Mudd's father passed away in 1877. In January of 1878 Dr. Mudd's youngest daughter and ninth child, Mary Eleanor ("Nettie"), was born. In January of 1883 Dr. Mudd had a busy schedule with many sick patients during a harsh winter. On New Year's Day he put on his muffler and overshoes and called on patients. He came down with a severe cold. He was running a fever and had to remain in bed. As the days progressed, the fever rose. On January 10th, 1883, Dr. Mudd died of pneumonia or pleurisy at the age of 49. He was buried in St. Mary's cemetery next to the Bryantown church where he first met Booth in 1864. Sarah Frances, who was buried next to him, lived until November 29, 1911.

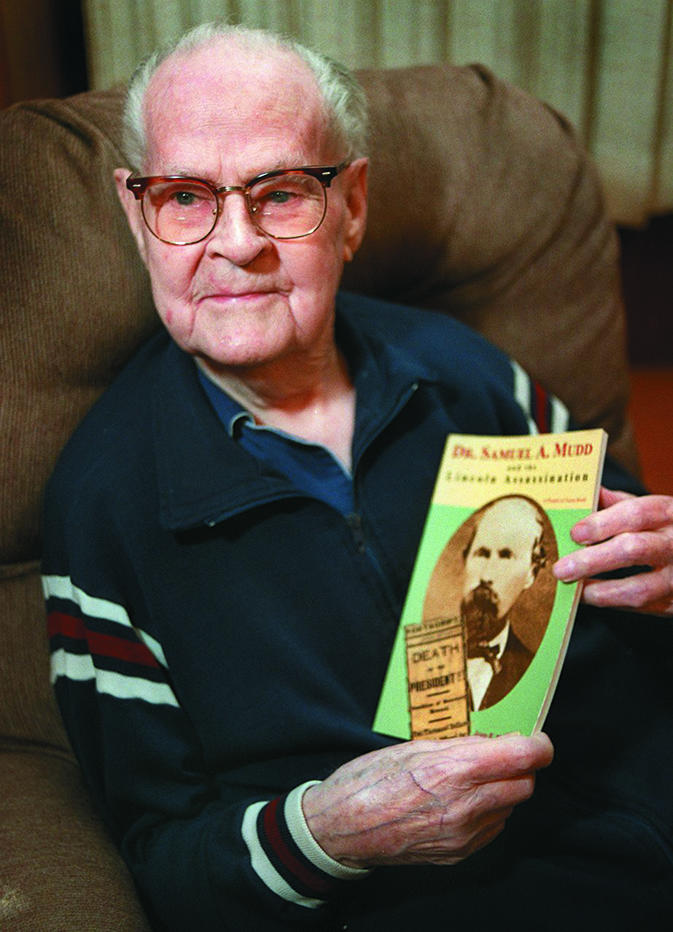

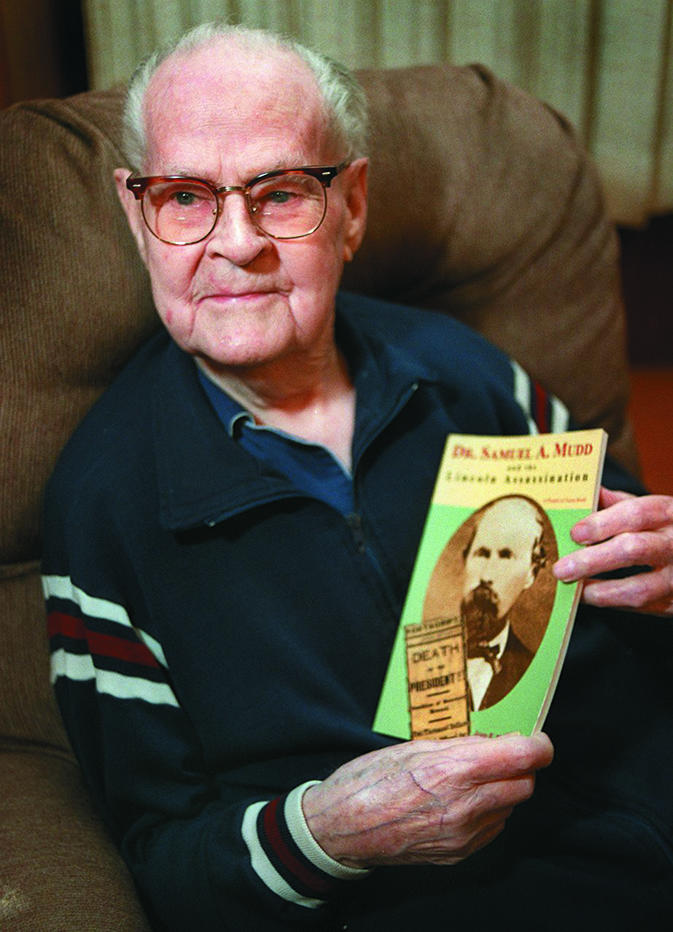

Dr. Mudd's descendants, most notably Dr. Richard Mudd (1901-2002) of Saginaw, Michigan, worked indefatigably to clear his name of any complicity with John Wilkes Booth. A petition (petitioner Richard D. Mudd, M.D.) was filed in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (case No. 1:97CVO2946) bringing suit against the Secretary of the Army, Togo West et.al., ordering the Archivist of the United States to "...correct the records in his possession by showing that Dr. (Samuel A.) Mudd's conviction was set aside pursuant to action taken under 10 U.S.C. sec. 1552.", and that the court "...order the payment of Petitioner's costs in bringing this action;..." On July 22, 1998, U.S. District Judge Paul Friedman said he would rule soon, and on Thursday, October 29, 1998, he ordered the Army to reconsider the conviction of Dr. Mudd. Friedman said the Army's recent rulings (see below) against the request were arbitrary. The following decision was announced on March 9, 2000: SAGINAW, Mich. (AP) - The U.S. Army has rejected an appeal to overturn the 1865 conviction of Dr. Samuel Mudd as an accomplice in the escape of John Wilkes Booth after the Lincoln assassination. Mudd's 99-year-old grandson, Dr. Richard Mudd of Saginaw, has waged a long campaign to clear his grandfather's name. But this week, Army Assistant Secretary Patrick T. Henry rejected the latest request to throw out Samuel Mudd's conviction by a military court. Henry said his decision was based on a narrow question - whether a military court had jurisdiction to try Samuel Mudd, who was a civilian. "I find that the charges against Dr. Mudd (i.e., that he aided and abetted President Lincoln's assassins) constituted a military offense, rendering Dr. Mudd accountable for his conduct to military authorities," he wrote in Monday's decision.

On March 14, 2001, Judge Friedman rejected Richard Mudd's contention that his grandfather should not have been tried by a military court because he was a citizen of Maryland, a state that did not secede from the Union, and thus entitled to a civil trial. John McHale, a Mudd family spokesman, said that an appeal of Judge Friedman’s ruling would be filed. On Friday, November 8, 2002, a federal appeals court dismissed the case. Judge Harry Edwards wrote that the law under which the Mudd family was seeking to have Samuel Mudd's conspiracy conviction expunged applied only to records involving members of the military. Although a military tribunal tried Mudd, he was not a member of the military.

For more information CLICK HERE. For more discussion CLICK HERE. |

PRO AND CON

In October of 1959 President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized the placing of a plaque at Fort Jefferson honoring Dr. Mudd's efforts there in the 1867 yellow fever outbreak. Both the Michigan State Legislature (Concurrent Resolution Number 126 adopted in July of 1973) and former President Jimmy Carter have stated their belief in Dr. Mudd's innocence. In a letter dated December 8, 1987, President Ronald Reagan stated his belief that Dr. Mudd was innocent of any wrongdoing. In 1992 the Army Board for the Correction of Military Records recommended that relief be granted Samuel Mudd and his family. William D. Clark, Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army, denied the Board's recommendation. In 1993 a mock trial was held at the University of Richmond. One of the defense attorneys was none other than F. Lee Bailey. The judges hearing the case (one of which was a member of the State Supreme Court of South Carolina) stated that Dr. Mudd's conviction had been a flagrant violation of the United States Constitution.

It must be noted, however, that professional historians and writers who have spent years studying and researching the case differ in their analysis of Dr. Mudd's guilt or innocence. In October 1997 a book titled "His Name is Still Mudd" was published. Written by noted Lincoln scholar Dr. Edward Steers Jr., the book presents the case against Dr. Mudd. It includes incriminating evidence against Dr. Mudd that most people are not generally aware of. CLICK HERE to order Dr. Steers' book. Although many assassination experts share Dr. Steers' beliefs about Dr. Mudd, this sentiment is certainly not unanimous among the professionals. However, given the current published research, it's difficult to argue that Mudd was simply an innocent country doctor who set an injured man's broken leg. On the other hand, it should definitely be noted that assassination expert Michael Kauffman makes a good case on Dr. Mudd's behalf in his 2004 publication American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies.

On Thursday, June 12, 1997, Rep. Steny Hoyer (D - Maryland) introduced in Congress The Samuel Mudd Relief Act of 1997. Co-sponsored by Rep. Thomas Ewing (R - Illinois), Rep. Robert Borsky (D-Pennsylvania), and Rep. Robert Ehrlich (R-Maryland), the bill, if passed and signed by President Clinton, would direct the Secretary of the Army to set aside the 1865 conviction of Dr. Mudd. In March 1996 Sara E. Lister, Assistant Secretary for the Department of the Army, declined to do what this bill seeks. In the April 1998 Surratt Courier, John E. McHale takes a detailed look at the legal aspects of Dr. Mudd's case and explains why he feels the government never proved any kind of complicity by Dr. Mudd. Dr. Edward Steers' equally detailed reply is in the June 1998 edition of the Courier. The July 1998 Courier contains articles on the lawsuit (written by Richard Willing) and further evidence of Dr. Mudd's complicity with Booth (written by the late renowned assassination expert Dr. James O. Hall). The September 1998 issue contains James E.T. Lange's views of the legal issues surrounding the case. In the October 1998 issue, Dr. Edward Steers supports the position taken in Dr. Hall's article in the August issue about whether or not the authorities showed Dr. Mudd a picture of JWB or his brother, Edwin. To subscribe to the Courier, Click Here.

Dr. Richard Mudd, who passed away at the age of 101 on Tuesday, May 21, 2002, argued vehemently and sincerely for the innocence of his grandfather. In a taped interview which I listened to on July 7, 1999, Dr. Mudd was extremely articulate, impressive, and eloquent in his arguments. Stacy Nelson conducted the interview with Dr. Mudd, and I would like to thank her for sending me a copy of the tape. The photo of Dr. Richard Mudd is from the Associated Press. The effort to exonerate Samuel Mudd will now be carried on by Richard Mudd’s son, Thomas B. Mudd.

|

|

|

|

Note: The above photos were personally taken c.1980. |

|

|

|

Others Tried By The Military Commission |

|

|

|

|