GEORGE ATZERODT |

Library of Congress Photograph

Library of Congress Photograph

|

George Andrew

Atzerodt was born on June 12, 1835, in Dorna, Prussia. In June 1844

he came to America with his folks and settled near Germantown in Montgomery County,

Maryland. Atzerodt never

became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Later the Atzerodt family moved to Westmoreland County, Virginia. In 1857, George Atzerodt’s father, Johann, passed away.

Before the Civil War started, Atzerodt settled in Port Tobacco, Maryland, with his older brother, John. Together, they set up a carriage repair shop. Although the business seemed to prosper, the two brothers eventually separated. John moved to Baltimore and George remained in Port Tobacco. ("Port Tobacco" became his nickname.)

During the Civil War, George began rowing his Confederate friends back and forth across the Potomac River. While engaged in this activity, he became acquainted with a Confederate messenger named John Surratt. The introduction came through Confederate agent Thomas H. Harbin and occurred in January of 1865. Atzerodt's knowledge of the back roads, escape routes, etc. impressed Surratt. Additionally, Surratt was looking for a boatman who could ferry the conspirators across the Potomac River after they had kidnapped President Lincoln. In time, Atzerodt was invited to Washington to meet John Wilkes Booth. He was also invited to the Surratt boardinghouse that was operated by John's mother, Mary.

He remained in an attic room at the boardinghouse for several days, but it is quite clear Mrs. Surratt did not like Atzerodt. While Atzerodt was out, Mary found liquor bottles in his room. She told her son, John, that Atzerodt had to move out because of his drinking.

Booth was attracted to Atzerodt because he saw him as a knowledgeable accomplice in the initial plan to kidnap Lincoln. On the night of March 15, 1865, Atzerodt met with Booth and other conspirators at Gautier's Restaurant on Pennsylvania Avenue to discuss the possible abduction of the president. These plans did not work out. Several days before the assassination, Booth told Atzerodt about the existence of a plot to blow up the White House. Atzerodt's statement regarding this alleged plot disappeared until the late 1970's when it was discovered by Joan Chaconas, then president of the Surratt Society.

|

|

The statement was found among the private papers of Atzerodt's attorney, William E. Doster. The plot, which never took place, was to mine that part of the White House nearest the War Department where Lincoln spent a lot of time. Among other things, this "lost" statement of Atzerodt's revealed that Booth had sent liquor and provisions to Dr. Samuel Mudd's home two weeks before the assassination. For more on this, see Dr. Edward Steers' book titled His Name is Still Mudd. For the text of Atzerodt’s statement, CLICK HERE.

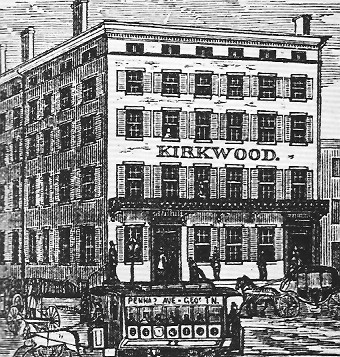

In the assassination plot, Atzerodt was assigned to kill Vice-President Andrew Johnson. Whether Atzerodt ever really agreed to do this is unproven. Whatever the case, before 8:00 A.M. on April 14th, 1865, Atzerodt rented room 126 at the Kirkwood House directly above where Johnson was staying. (The Kirkwood House was torn down after the Civil War; an office building now stands at the site on the northeast corner of 12th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. The drawing to the right is from the National Park Service.) Atzerodt quizzed the Kirkwood House's bartender, Michael Henry, about the vice-president's character and habits. However, he made no attempt on the life of Andrew Johnson. At his trial, Atzerodt's lawyer said, "Atzerodt was guzzling like a Falstaff at 10:15 P.M. After Lincoln's assassination, Detective John Lee found a series of incriminating items in Atzerodt's rented room left there by David Herold.

|

|

|

|

National Archives Photograph of Andrew Johnson

Atzerodt was arrested on April 20th at the home of his cousin, Hartman Richter, in Germantown, Maryland. Atzerodt was charged with being a party to the assassination conspiracy, and he was tried along with the others. Things did not go well for him in the courtroom. His appearance was described by spectators as "stupid and crafty." Like Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, and David Herold, Atzerodt was found guilty and sentenced to hang. On July 7, 1865, he was executed. In his strong German accent, his last words were, "Good-by, gentlemen. May we all meet in the other world!"

The tradtional story is that George Atzerodt was originally buried in an unmarked grave in Glenwood Cemetery north of the Capitol in Washington. Later his remains were moved to St. Paul’s Cemetery in Baltimore. He was buried under the fictitious name of Gottlieb Taubert. However, new information has been discovered that makes his final resting place a mystery.

There are at least four known statements of George Atzerodt in addition to the one discovered by Joan Chaconas. There is a statement given to Frank Monroe aboard the USS Saugus on April 23, 1865. There is the statement given to Col. H.H. Wells aboard the USS Montauk on April 25, 1865. There is a statement published in the Baltimore American on January 18, 1869. There is a statement read by attorney William E. Doster on June 21, 1865.

NOTE: The information on the plot to blow up the White House came from an article by noted Lincoln scholar, Dr. William Hanchett, in the December 1995 issue of Civil War Times Illustrated. Also, see p. 172 of the late William A. Tidwell's April '65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War and the Appendix and Notes of His Name is Still Mudd by Dr. Edward Steers. For more details on Atzerodt, please see the biography of George Atzerodt in the December 2000 edition of the Journal of the Lincoln Assassination. |

|

|

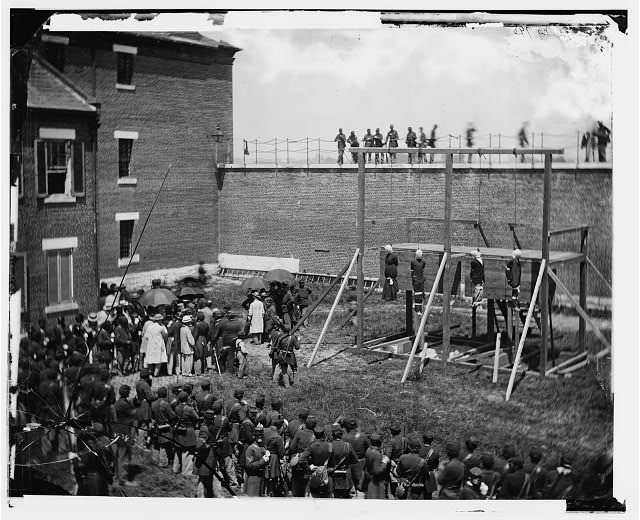

THE EXECUTION - JULY 7, 1865, AT 1:26 P.M.

Left to right: Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt. |

|

Others Tried By The Military Commission |

|

|

|

This is not a commercial website. None of the photographs and artwork exhibited herein are being sold by the webmaster. Some photographs and artwork are believed to be in the public domain. Any copyrighted photographs and artwork are used in the context of this website strictly for educational, research and historical purposes only, under the "Fair Use" provisions of the Copyright Act, (US CODE: Title 17,107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair Use Section 107). Anyone claiming copyright to any of the posted photographs or artwork please inform the webmaster of such and it will be duly noted or removed.

Questions, comments, corrections or suggestions can be sent to R. J. Norton, the creator and maintainer of this site. All text except reprinted articles was written by the webmaster, ©1996-2019. All rights reserved. It is unlawful to copy, reproduce or transmit in any form or by any means, electronic or hard copy, including reproducing on another web page, or in any information or retrieval system without the express written permission of the author. The website was born on December 29, 1996.

Web design by Andrew Patel.

|