Abraham Lincoln's Last Day

|

7:00 A.M.

As usual the president arose at seven. Friday, April 14, 1865, began as a lovely spring day in Washington, D.C. The dogwood trees were in bloom, and there was a scent of fresh flowers in the air. The willows along the Potomac River were green. In the parks and gardens the lilacs bloomed. Before breakfast Mr. Lincoln, 56, went to his office, sat down at an upright mahogany desk and worked for awhile. Behind him was a velvet bell cord which he pulled to summon a secretary. The president left instructions for Assistant Secretary of State Frederick Seward to call a Cabinet meeting at 11:00 A.M. (Secretary of State William Seward was confined to bed due to a carriage accident.) Mr. Lincoln also wrote a note inviting General Ulysses S. Grant to attend the Cabinet meeting. |

|

8:00 A.M.

Abraham Lincoln ate breakfast. Normally he had one egg and one cup of coffee. This morning Mary Todd Lincoln, 46, sat at the opposite end of the table with sons, Robert, 21, and Tad, 12, at the sides. President Lincoln listened as Captain Robert Lincoln discussed his brief tour of duty in the Union Army. Robert had been present at the Mclean House in Appomattox when General Robert E. Lee surrendered. Mary said she had tickets to Grover's Theatre, but she'd prefer to see Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. She also indicated a hope that General and Mrs. Grant would accompany them to the theater. After breakfast the president excused himself to go back to work in his office which was located in the southeast corner of the White House. |

|

9:00 A.M.

Lincoln read the morning newspapers. His first visitor of the day was Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax. Lincoln told the Speaker his own ideas as to what the future policy should be toward the Southern states. Colfax expressed a concern that Lincoln would proceed with reconstruction without legislative branch consultation. At the War Department General Grant told Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that the Grants were going to decline the Lincolns' theater invitation. |

|

10:00 A.M.

Mr. Lincoln greeted more visitors. One of them was former New Hampshire Senator John P. Hale who had recently been appointed minister to Spain. (Hale's daughter, Lucy, was John Wilkes Booth's fiancée.) Mr. Lincoln then called for a messenger and requested that he go to Ford's Theatre and reserve the State Box for the evening's performance. He did not yet know General Grant intended to decline the invitation and leave Washington on a late afternoon train. The management of Ford's was elated when they heard the news of their special guests for Good Friday's Our American Cousin performance. |

|

11:00 A.M.

The president began the scheduled meeting of his Cabinet. Stanton, as usual, arrived late. Grant was present at the meeting, and Lincoln was expecting important deliberations regarding reconstruction to occur. He admitted he was open to suggestions on this very complex matter. Lots of various ideas were proposed to begin the process of reconciliation between North and South. Also discussed was what to do with the leaders of the Confederacy. Lincoln spoke from the heart when he said, "... enough lives have been sacrificed." |

|

12:00 Noon

The Cabinet meeting continued with more discussion of the process of putting the country on its feet again. |

|

1:00 P.M.

Except for minor differences of opinion, the Cabinet seemed agreed that helping the South economically would also be beneficial to the North. At this point, the president asked General Grant to describe the details of General Lee's surrender. Vice-President Andrew Johnson arrived at the White House. With the Cabinet meeting still in progress, Johnson decided to take a walk and wait until Lincoln could see him.

|

|

2:00 P.M.

The Cabinet meeting ended. Grant got up from his chair and walked over to Mr. Lincoln. The general explained he and his wife would not be going to Ford's Theatre; rather they were taking the evening train out of Washington to visit their children. At about 2:20 Lincoln left the office for lunch with Mary. Although no record of the lunch time conversation exists, it's quite likely Abraham told Mary that the Grants would not be accompanying them to see Our American Cousin. Lincoln, back at work, studied some papers dealing with an army deserter. He signed a pardon, and made the remark, "Well, I think the boy can do us more good above ground than underground." |

|

3:00 P.M.

Andrew Johnson and Mr. Lincoln met for approximately 20 minutes. Then the president met with a former slave named Nancy Bushrod. Her husband had served in the Union Army, but he was missing some paychecks. Lincoln promised to look into the matter. At the War Department, the Stantons decided to "send regrets" about attending Our American Cousin with the Lincolns that evening. |

|

4:00 P.M.

Lincoln had finished his day's work. Mary wished to go for a carriage ride. The president met briefly with Charles A. Dana, Assistant Secretary of War.

|

|

5:00 P.M.

Congressman Edward H. Rollins of New Hampshire stopped by to get a pass for a constituent to go and see his wounded son in an army hospital. The president and his wife came out on the White House porch. A one-armed soldier, hoping to catch sight of Mr. Lincoln, yelled, "I would almost give my other hand if I could shake that of Abraham Lincoln." The president walked toward the soldier and grabbed his hand. Lincoln said, "You shall do that and it shall cost you nothing." The Lincolns then entered the carriage with Francis P. Burke, their coachman, as the driver. Two cavalrymen followed the carriage as it started down the gravel White House driveway. The carriage arrived at the Navy Yard, and the president took a short stroll on the deck of the monitor Montauk. Then he got back in the carriage for the short trip back to the White House.

|

|

6:00 P.M.

The carriage pulled into the White House driveway. Two old friends from Illinois, Dick Oglesby and General Isham N. Haynie, greeted the president. He invited them into his office for a friendly discussion of 'old times.' Word that dinner was ready reached Lincoln, and his old friends excused themselves. The Lincolns ate as a family. Mary told Abraham that a young couple, Clara Harris, 20, and Major Henry Rathbone, 28, had accepted a Ford's Theatre invitation. (Rathbone's townhouse at 712 Jackson Place in Lafayette Square still stands.) The Lincolns would pick up the couple at the Harris residence on H Street near Fourteenth. |

|

7:00 P.M.

William H. Crook, the president's bodyguard, was relieved three hours late by John F. Parker. Parker was told to be on hand at Ford's Theatre when the presidential party got there. Crook said, "Good night, Mr. President." Lincoln responded, "Good-by, Crook." According to Crook, this was a first. Lincoln had always previously said, "Good night, Crook." Speaker of the House Colfax visited the president for a second time that day. Lincoln told him he had decided not to call a special session of Congress to deal with reconstruction. Colfax left, and at 7:50 former Congressman George Ashmun arrived without an appointment. Lincoln decided to see Ashmun anyway. |

|

8:00 P.M.

|

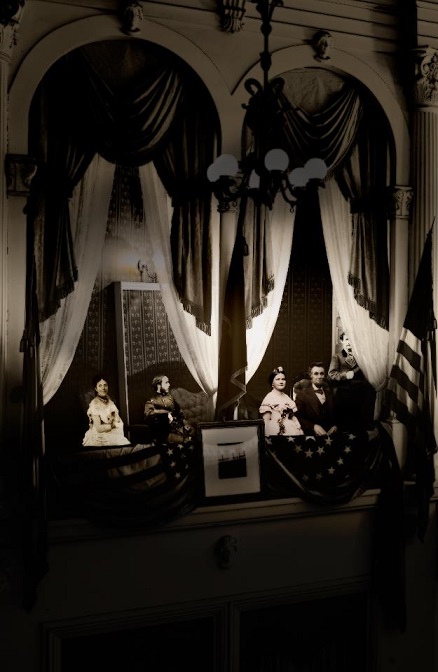

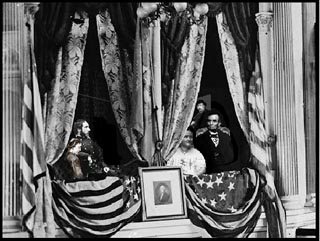

At 8:05 Lincoln's business with Ashmun was still unfinished, and he requested a return visit in the morning. Lincoln wrote out the last message of his life: "Allow Mr. Ashmun & friend to come in at 9:00 A.M. tomorrow." The note was signed "A. Lincoln, April 14, 1865." He and Mrs. Lincoln then went out the front door of the White House to the waiting carriage. (The carriage is on display at the Studebaker National Museum. There is a photograph of it on the museum’s website.) Mary wore a black and white striped silk dress and a matching bonnet; Abraham wore a black overcoat and white kid gloves. Lincoln's coat was made of wool and had been tailored for him by Brooks Brothers of New York. The weather had changed; it was a foggy, misty night. On the way to Ford's, the carriage stopped to pick up Clara Harris and Henry Rathbone. (Both of whom are pictured to the left; the photo of Clara is from the Associated Press, and the photo of Henry is from the National Archives.) The carriage proceeded to Ford's. Clara Harris and Major Rathbone faced the Lincolns, riding backwards. Also in the carriage were Burke, the coachman, and Charles Forbes, Lincoln's valet. They arrived at Ford's at about 8:30 P.M. The play had already begun. John M. Buckingham, Ford's main doorkeeper and ticket collector, greeted the honored guests. John Parker led the presidential party as it entered the theater and walked towards the State Box. The play stopped, and the orchestra played "Hail to the Chief." People in the audience stood and politely clapped. Once the president was seated, Our American Cousin resumed. His chair was a black walnut one with red upholstery. It had been brought down from the Ford family's personal quarters located on the 3rd floor above Taltavul's Star Saloon.

|

|

|

|

9:00 P.M.

Our American Cousin continued before over 1,000 patrons in the theater. At one point, Abraham Lincoln felt a chill. Mary asked if he wanted a shawl, but the president rose and put on his black coat instead. He sat back in his rocking chair (which was out of view of the vast majority of the audience). During the play's intermission, John F. Parker, the president's bodyguard, left the theater and went next door to Taltavul's Star Saloon for a drink. He was not at his post when Act III of the play began. |

|

10:00 P.M.

Our American Cousin was now in its third act. Mary sat very close to her husband, her hand in his. She whispered to him, "What will Miss Harris think of my hanging on to you so?" The president replied, "She won't think anything about it." It was between 10:15 P.M. and 10:30 P.M. On stage actor Harry Hawk was saying, "Don't know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal - you sockdologizing old mantrap!" John Wilkes Booth came up behind Mr. Lincoln and shot him in the back of the head near point blank range. The bullet entered the head about 3 inches behind the left ear and traveled about 7 1/2 inches into the brain. Major Rathbone thought Booth shouted a word that sounded like "Freedom!" (Many accounts have Booth yelling "Sic Semper Tyrannis" in the box, or when he landed on the stage.) Booth struggled briefly with Rathbone, stabbed him with a knife, leaped 11 feet to the stage, broke the fibula bone in his left leg, and escaped from the theater. (At least one assassination expert, Michael Kauffman, feels Booth did not break his leg in his leap to the stage. Kauffman feels Booth broke his leg later that night when his horse took a fall.) Lincoln's head inclined toward his chest, and Mrs. Lincoln screamed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first doctor to attend the president was 23 year old Charles Leale. After examining the stricken man he sadly said, "His wound is mortal. It is impossible for him to recover." It was decided to move the president, and his comatose body was carried across the street to the Petersen House whose address was 453 Tenth Street (nowadays 516 Tenth Street). |

|

To the right is a contemporary drawing of the Petersen House on the night of the assassination. Armed soldiers guard the house as the president is cared for inside. (The drawing is from the Library of Congress.)

The president was placed diagonally on a bed in a room rented by William T. Clark (pictured to the left; the photo of Clark came from p. 49 of WHEN LINCOLN DIED: The Assassination, The Funeral Journey, The Pursuit and Trial of the Conspirators, The Complete Story in Pictures and in the Words of His Day by Ralph Borreson), an army clerk. It was a small, neat room which measured 9 1/2 by 17 1/2 feet. Lincoln's pulse was 44, and his breathing was heavy. He was cold to the touch.

|

|

|

A nightlong deathwatch began. Nearly every leading doctor in Washington D.C. stopped by to offer help and assistance. A large crowd gathered outside in front of the Petersen House. The president's breathing grew fainter; although the doctors felt an average man with this kind of wound would die within two hours, Mr. Lincoln lasted for nine. He passed away the next morning at 7:22 A.M. + 10 seconds, April 15th, 1865. Mrs. Lincoln was informed, "It is all over. The president is no more!" Back in Illinois, when Mr. Lincoln's stepmother heard the news, she said, "I knowed they'd kill him. I ben awaiting fur it." Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton said, "Now he belongs to the ages." |

|

The photograph above was taken by Petersen House boarder Julius Ulke shortly after the president died. Shortly before it was taken, Mr. Lincoln's body lay diagonally on this bed. Source: Chicago History Museum.

Amazingly, during the previous month, John Wilkes Booth had rested on this exact same bed. In March 1865 actor John Mathews had rented the room. One day Booth visited Mathews and fell asleep on the very same bed President Lincoln later died upon.

|

|

NOTE #1: In 1956 the last surviving person who was in Ford's Theatre the night of the assassination passed away. His name was Samuel J. Seymour. He was 96 years old when he died. He lived in Arlington, Virginia. At age 5 his godmother, Mrs. George S. Goldsborough, had taken him to see Our American Cousin. The two sat in the balcony on the side opposite Lincoln's box.

SAMUEL JAMES SEYMOUR

NOTE #2: The marriage of Clara Harris and Henry Rathbone took place July 11, 1867, in Albany, New York. Living in Germany in 1883, Henry went berserk two days before Christmas, shot and stabbed Clara to death and spent the rest of his life in an insane asylum. He died in 1911 at the age of 73.

NOTE #3: The contents of Mr. Lincoln's pockets on the night of the assassination are on display at the Library of Congress. For more information on this, CLICK HERE.

NOTE #4: Andrew Johnson was sworn in as president at 10:00 A.M. on the morning of April 15th. The ceremony took place in Johnson's room at the Kirkwood House, and Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase administered the oath. If Johnson had also been assassinated as Booth planned, Senate President Pro Tempore Lafayette S. Foster of Connecticut would have become acting president pending an election of a new president. The process of electing a new president could only be set in motion by the secretary of state; thus Booth felt Seward's assassination would throw the Union government into "electoral chaos." A Presidential Succession law passed on March 1, 1792, was still in effect in 1865. It provided that the president pro tempore of the Senate was third in line to the presidency and the Speaker of the House was fourth. This law didn't make any succession provisions beyond the Speaker.

|

|

Although the information contained on this page was gathered using many sources (see the bibliography here), I have used Jim Bishop's The Day Lincoln Was Shot for the page's basic outline.

|

|

For many fascinating facts not only about the assassination (and its aftermath) but also about Washington, D.C. sites in general please see Albert E. Kennedy's excellent book entitled JUST THE FACTS ABOUT WASHINGTON, D.C. The book answers over 2,500 questions about 34 historical sites in and around Washington. To learn details on this valuable publication please CLICK HERE. |

|

A new hardback edition of Clara E. Laughlin's The Death of Lincoln: The Story of Booth's Plot, His Deed, and the Penalty has been published. Laughlin's book was originally published on February 9, 1909, the centennial of Lincoln's birth. The new edition contains an index and a preface by Lincoln scholar, Michael W. Kauffman. If you would like to obtain a copy, contact Tony O'Connor's Vt. Civil War Enterprises at (802) 766-4747 or send e-mail to vtcwe@hotmail.com |

|

|

|

Many thanks to Chris Hunter for sending me the image at the top of the page. Most historians feel Booth actually approached Lincoln from the opposite side from what is shown in the image. This is because Booth mostly likely entered the box through door #8, not door #7.

The sketch of the stricken president is the work of James Warner. James Warner lives in Cadillac, Michigan and enjoys illustrating, woodcarving and antique collecting. To contact Mr. Warner for artwork please call (231) 577-4207 or send e-mails to: jameltrib@yahoo.com. Please type "Lincoln" in the subject line of your e-mail. Mr. Warner always enjoys hearing from people. However, all mail without the name "Lincoln" in the subject line will NOT be answered. Sorry for the inconvenience. ARTWORK NOT TO BE REPRODUCED FOR USE ON ANY OTHER SITE WITHOUT PERMISSION! |

|