|

"Our country owed all her troubles to him, and God simply made me the instrument of his punishment" |

|

THE LIFE AND PLOT OF JOHN WILKES BOOTH |

John Wilkes Booth was born on a farm near Bel Air, Maryland, about 25 miles from Baltimore. His birth date was May 10, 1838. He was the ninth of ten children of Junius Booth and Mary Ann Holmes. John's parents were British and had moved to the United States in 1821. In addition to the farm at Bel Air (where the Booth family had slaves), the family also owned a home on North Exeter Street in Baltimore where the colder months of the year were spent. Junius was one of the most famous actors on the American stage although he was an eccentric personality who had problems with alcohol and spells of madness.

As a young man John attended several private schools including a boarding school operated by Quakers at Cockeysville.

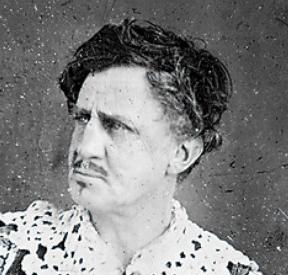

John Wilkes Booth's Parents

John Wilkes Booth's Parents

One day a gypsy living in the woods near Cockeysville read John's palm. She said, "Ah, you've a bad hand; the lines all cris-cras! It's full enough of sorrow. Full of trouble. Trouble in plenty, everywhere I look. You'll break hearts, they'll be nothing to you. You'll die young, and leave many to mourn you, many to love you too, but you'll be rich, generous, and free with your money. You're born under an unlucky star. You've got in your hand a thundering crowd of enemies - not one friend - you'll make a bad end, and have plenty to love you afterwards. You'll have a fast life - short, but a grand one. Now, young sir, I've never seen a worse hand, and I wish I hadn't seen it, but every word I've told is true by the signs. You'd best turn a missionary or a priest and try to escape it."

|

|

As a teenager Booth attended St. Timothy's Hall, an Episcopal military academy in Catonsville, Maryland. During the 1850's young Booth apparently became a Know-Nothing in politics. The Know-Nothing Party was formed by American nativists who wanted to preserve the country for native-born white citizens.

Booth eventually left school after his father died in 1852. He spent several years working at the farm near Bel Air. However, according to his sister, Asia Booth Clarke, Booth's dreams went beyond working at a farm. "I must have fame! fame!" he cried. His goal was to be a famous actor like his father had been.

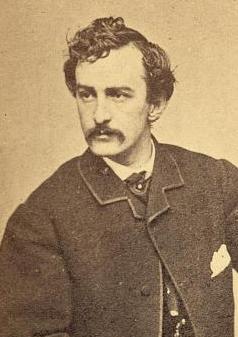

The photograph to the right is from the Library of Congress.

In August, 1855, when he was only 17 years old, Booth made his stage debut as the Earl of Richmond in Shakespeare's Richard III. Two years passed before he made another appearance on stage. In 1857 Booth played stock in Philadelphia, but he frequently missed cues and forgot his lines. He persevered, however, and came of age in 1858 as a member of the Richmond Theatre. It was in Richmond where he truly became enamored with the Southern people and way of life. As his career gained momentum, many called him "the handsomest man in America." He stood 5-8, had jet black hair, ivory skin, and was lean and athletic. He had an easy charm about him that attracted women.

|

|

|

|

In 1859 Booth was an eyewitness to the execution of John Brown, the abolitionist who had tried to start a slave uprising at Harpers Ferry. Wearing a militia uniform, Booth stood near the scaffold with other armed men to guard against any attempt to rescue John Brown before the hanging.

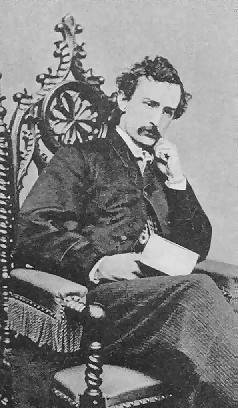

The photograph to the left is from Asia Booth Clarke's The Unlocked Book.

In 1860 Booth's career as an actor took off. Soon he was earning $20,000 a year. He invested some money in the oil business. He was hailed as the "youngest tragedian in the world." He was playing the role of Duke Pescara in The Apostate at the Gayety Theater in Albany, New York, as President-elect Abraham Lincoln passed through on his way to Washington. Over the next several years he starred in Romeo and Juliet, The Apostate, The Marble Heart, The Merchant of Venice, Julius Caesar, Othello, The Taming of the Shrew, Hamlet, and Macbeth among others.

The photograph to the right is from the Library of Congress.

|

|

|

|

|

Booth appeared in New York, Boston, Baltimore, Washington, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, St. Louis, Leavenworth, Richmond (before the Civil War), Nashville, New Orleans and several other cities. On November 9, 1863, President Lincoln viewed Booth in the role of Raphael in The Marble Heart. Besides appearing at Ford's from November 2 to November 15, 1863, Booth made only one other acting appearance in that theater. That occurred on March 18, 1865, when Booth made the last appearance of his career as Duke Pescara in The Apostate.

When the Lincolns saw John Wilkes Booth in "The Marble Heart" at Ford's Theatre on November 9, 1863, they were accompanied by several people. Among these people was Mary B. Clay, a daughter of Cassius Clay, U.S. minister to Russia. Mary Clay reminisced about the evening as follows: "In the theater President and Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Sallie Clay and I, Mr. Nicolay and Mr. Hay, occupied the same box which the year after saw Mr. Lincoln slain by Booth. I do not recall the play, but Wilkes Booth played the part of villain. The box was right on the stage, with a railing around it. Mr. Lincoln sat next to the rail, I next to Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Sallie Clay and the other gentlemen farther around. Twice Booth in uttering disagreeable threats in the play came very near and put his finger close to Mr. Lincoln's face; when he came a third time I was impressed by it, and said, 'Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you.' 'Well,' he said, 'he does look pretty sharp at me, doesn't he?' At the same theater, the next April, Wilkes Booth shot our dear President. Mr. Lincoln looked to me the personification of honesty, and when animated was much better looking than his pictures represent him." Mary Clay, in her reminiscence, was off by a year when she said the president was shot "the next April."

SOURCE: p. 243 of Mary, Wife of Lincoln by her niece Katherine Helm (New York, Harper and Brothers, 1928). Note: Historians have raised questions about this story. It may be apocryphal.

|

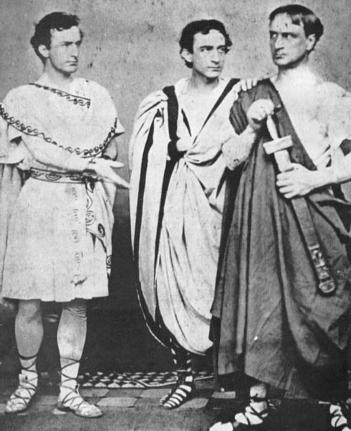

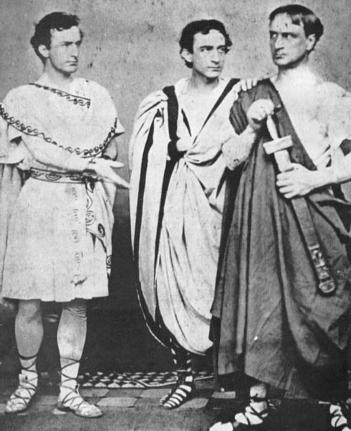

On November 25, 1864, before a standing room only crowd in New York, Booth (along with his two brothers) played the role of Marc Anthony in Julius Caesar. Critics generally rated John Wilkes Booth as a good actor, but he was considered below the talent level of his father and older brother, Edwin.

|

|

|

Pictured to the left are the three Booth brothers in Julius Caesar. From the left, John played Marc Anthony, Edwin played Brutus, and Junius played Cassius. The photograph is in the McClellan Collection at Brown University.

In the spring of 1862 Booth was arrested and taken before a provost marshall in St. Louis for making anti-government remarks. He told Asia, "So help me holy God! my soul, life, and possessions are for the South."

In the summer and possibly the fall of 1864 Booth occasionally stayed at the McHenry House in Meadville, Pennsylvania. It is known that he registered at the McHenry House on June 10, 1864, and again on June 29, 1864. Most likely his stops in Meadville were to make railroad connections. Scratched on a windowpane in room 22 in the McHenry House were the words "Abe Lincoln Departed This Life August 13th, 1864 By The Effects of Poison." After the assassination, these words drew attention because of Booth's association with David Herold, a druggist's clerk with easy access to poison. Although there has been much speculation as to who may have scratched these words, Booth was not an occupant of the room where the words were scratched.

|

|

"This country was formed for the white not for the black man. And looking upon African slavery from the same stand-point, as held by those noble framers of our Constitution, I for one, have ever considered it, one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us) that God ever bestowed upon a favored nation."

John Wilkes Booth, November, 1864, in a letter to his brother-in-law

|

|

|

|

It's unlikely Booth scratched these words into a windowpane at the McHenry House. |

|

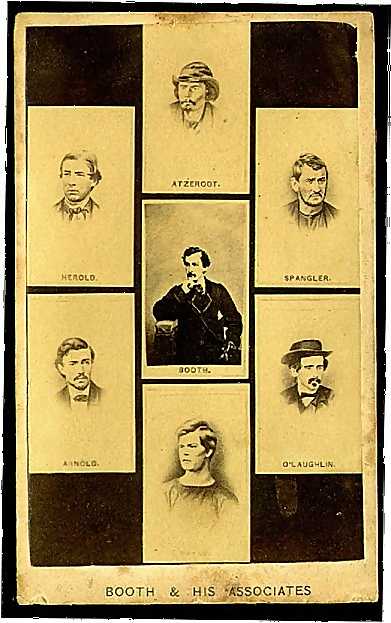

In the late summer of 1864 Booth began making plans to kidnap Abraham Lincoln. The president would be seized, taken to Richmond, and held in exchange for Confederate soldiers in Union prison camps. This would be a way of swelling the dwindling ranks of Confederate armies. Booth began recruiting a gang of conspirators. Within several months, he had recruited Michael O'Laughlen, Samuel Arnold, Lewis Powell (alias Paine or Payne), John Surratt, David Herold, and George Atzerodt. On March 15th Booth met with the entire group at Gautier's Restaurant on Pennsylvania Avenue about three blocks from Ford's Theatre to discuss Lincoln's abduction. Shortly thereafter, Booth learned that Lincoln would be attending a play (Still Waters Run Deep) at the Campbell Hospital just outside Washington on March 17, 1865. It seemed like an ideal time to seize Lincoln in his carriage. However, at the last minute, Booth learned that the president was not going to attend the performance. Rather than attend the play, Lincoln had decided instead to speak to the 140th Indiana Regiment and present a captured flag to the Governor of Indiana. After this failure, some of the conspirators began to "melt" away.

Some Lincoln assassination books say an actual attempt was indeed made to kidnap the president on March 17, 1865. But when the conspirators realized it wasn't Lincoln in the carriage they rode off in disgust. This story is probably untrue and the incident never really took place. See p. 150 in Samuel Bland Arnold: Memoirs of a Lincoln Conspirator edited by Michael W. Kauffman. It seems likely that John H. Surratt embellished the story in his lecture on the conspiracy.

"He (Booth) became a monomaniac on the success of the Confederate arms, a condition which generally follows when a man's thoughts are constantly centered upon one subject alone."

Samuel B. Arnold, December 20, 1902, (in the Baltimore American).

|

|

|

|

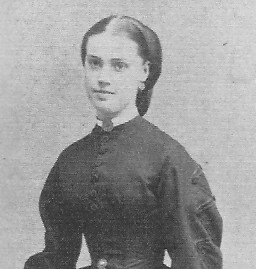

Booth had many lady friends. In the spring of 1864 he met a young Boston girl named Isabel Sumner. Isabel, only 16 years old, was very pretty, and Booth exchanged photographs and letters with her. |

|

Pictured to the left is Isabel Sumner. Source: "Right or Wrong, God Judge Me" The Writings of John Wilkes Booth edited by John Rhodehamel and Louise Taper.

He gave Isabel a ring, set with a pearl, which was inscribed "J.W.B. to I.S." When Booth was sick in New York Isabel sent him flowers. It seems the romance was short-lived, and there is no evidence it lasted beyond the summer of 1864.

|

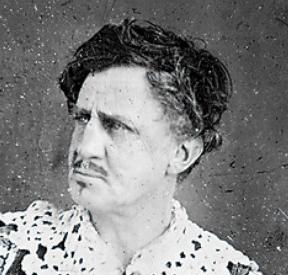

Sometime in late 1864 or early 1865, Booth entered into a serious romance with Lucy Lambert Hale, daughter of John Parker Hale, New Hampshire's abolitionist former senator.

(To the right is a National Park Service photo of Lucy.)

In January of 1865 the Hales moved into the National Hotel where Booth was staying. (President Lincoln named John Hale to be minister to Spain, and the Hale family was making preparations to sail to Europe.) By March Booth was secretly engaged to Lucy Hale. On March 4th Booth attended Lincoln's second inauguration as the invited guest of Lucy. Booth is known to have confided to his actor friend Samuel Knapp Chester, "What an excellent chance I had to kill the President, if I had wished, on inauguration day!" Booth was seen with Lucy at the National Hotel on the morning of the assassination.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Booth's other kidnap plans, such as seizing Lincoln inside a theater, fell through. On April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox. On April 11 the president gave his last speech from the White House. Booth, Herold, and Powell were in the audience. Among other things, Lincoln discussed possible new rights for certain blacks. He suggested conferring voting rights "on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers." Booth was enraged! He said, "Now, by God! I'll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make."

Three days later, on April 14, Booth stopped at Ford's Theatre to pick up his mail. While there he learned of President Lincoln's plans to attend the evening performance of Our American Cousin. For a detailed account of Booth's activities on the day of the assassination, CLICK HERE.

After the assassination Booth escaped from Washington, D.C. and was on the run for 12 days. He and David E. Herold, a co-conspirator, were sleeping in a tobacco barn owned by Richard H. Garrett on the morning of Wednesday, April 26, 1865, when Union cavalry finally caught up with them. In the vicinity of 2:00 A.M. the soldiers surrounded the barn which was located about 60 miles south of Ford's Theatre near Port Royal, Virginia. Herold gave up but Booth refused. The barn was set on fire, and Booth was shot by Boston Corbett. Booth's body was dragged out of the burning barn. For a short time the dying man was placed on the grass near a locust tree. Soon, though, the body was moved to the front porch of the Garrett home. Booth was paralyzed and barely alive. Sometime around 7:00 A.M. Booth looked at his hands and moaned, "Useless! Useless!" Those were the last words Booth spoke before dying.

For much more information on Booth's final words please see the article entitled The Last Words of John Wilkes Booth...Or Were They? by Dr. Blaine V. Houmes in the June 2007 edition of the Surratt Courier. Additional information can also be found in Frederick Hatch's article entitled "Let Me Die Bravely - The End of John Wilkes Booth" in the August 1998 edition of the Journal of the Lincoln Assassination.

|

|

For a closer look at the last few hours of Booth's life and the positive identification of his body, CLICK HERE. For the details of Booth's autopsy, CLICK HERE.

|

|

"For six months we had worked to capture. But, our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done."

Quote from John Wilkes Booth's diary. CLICK HERE to read the entire text of Booth's diary. |

|

|

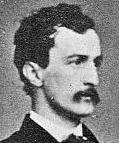

The rare carte-de-visite to the right was graciously contributed to this website by an anonymous donor.

Some authors have suggested Booth was most likely an agent or spy for the South. During the war he smuggled quinine and perhaps other medicines to the rebel army. Coded letters discovered in his trunk back at the National Hotel connected him to the Confederacy. When he was in Philadelphia, he often stayed with Asia. She recalled how "strange men called late at night for whispered consultations." In The Unlocked Book Asia wrote that she then knew "that my hero (JWB) was a spy, a blockade-runner, a rebel...I knew that he was today what he had been since childhood, an ardent lover of the South and her policy, an upholder of Southern principles. He was a man so single in his devotion, so unswerving in his principles, that he would yield everything for the cause he espoused." That he did.

For a detailed look at the evidence of the Confederate underground and its plans to kidnap or assassinate Lincoln see Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln by William A. Tidwell with James O. Hall and David Winfred Gaddy and April '65: Confederate Covert Action and the American Civil War by William A. Tidwell. For a fascinating look inside Booth's mind, see "Right or Wrong, God Judge Me" The Writings of John Wilkes Booth edited by John Rhodehamel and Louise Taper. For a detailed look at Booth through the eyes of a conspirator (plus the very difficult existence at Ft. Jefferson) see Samuel Bland Arnold: Memoirs of a Lincoln Conspirator edited by Michael W. Kauffman. Eleanor Ruggles' Prince of Players: Edwin Booth also contains lots of information about JWB. Yet another excellent source is John Wilkes Booth: A Sister's Memoir by Asia Booth Clarke edited by Terry Alford. This is the source of the account of the gypsy. Additionally there are Francis Wilson's John Wilkes Booth: Fact and Fiction of Lincoln's Assassination, Stanley Kimmel's The Mad Booths of Maryland, and Terry Alford's Fortune's Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth. For a look at why Booth also wanted Secretary of State William Seward assassinated, see the Spring 1998 edition of The Lincoln Herald. The quote at the very top of the page is contained in Booth's dairy. The photo of Booth's mother came from Francis Wilson's book. The image of the windowpane at the McHenry House came from page 396 of Lincoln's Assassins: A Complete Account of Their Capture, Trial and Punishment by Roy Z. Chamlee, Jr.

Please visit Spirits of Tudor Hall for fascinating additional information.

Also, be sure to visit the BoothieBarn Blog!.

|

|

| |

** Verifying information about Booth's March 17 kidnap plans was cited by the late Lincoln assassination scholar, Dr. James O. Hall, during an interview published in the April 1990 edition of the Journal of the Lincoln Assassination. Dr. Hall said that E.L. Davenport, an actor in the play at Campbell Hospital, recalled how Booth had arrived at the hospital and asked about Lincoln's whereabouts on the afternoon of March 17, 1865.

|

|

|

Dave Taylor's BoothieBarn - Discovering the Conspiracy

Lincoln assassination expert and researcher Dave Taylor now has his own blog. To learn fascinating information about the assassination please CLICK HERE.

|

|

|

Kieran McAuliffe has reissued and updated his John Wilkes Booth Escape Route Map

Follow the route taken by the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln as he fled from Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865, until his capture and death 12 days later at the Garrett Farm in Virginia. Completely updated inside and out. Presenting the latest research into the escape attempt of John Wilkes Booth after he assassinated President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. Booth's escape route and the search routes are clearly shown and color coded. Follow the fugitives and the soldiers day by day, hour by hour. A 1200-word commentary details the assassination, the escape, and the capture and death of Booth. 34 pictures and illustrations are included. Convenient size. No awkward unfolding as with traditional maps. Folded map measures 5 by 11 inches. Unfolds to 11 by 20. A must for anyone reading a book on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

To order please CLICK HERE.

|

|

|

The sketch of Booth dying on Garrett's porch is the work of James Warner. James Warner lives in Cadillac, Michigan and enjoys illustrating, woodcarving and antique collecting. To contact Mr. Warner for artwork please call (231) 577-4207 or send e-mails to: jameltrib@yahoo.com. Please type "Lincoln" in the subject line of your e-mail. Mr. Warner always enjoys hearing from people. However, all mail without the name "Lincoln" in the subject line will NOT be answered. Sorry for the inconvenience. ARTWORK NOT TO BE REPRODUCED FOR USE ON ANY OTHER SITE WITHOUT PERMISSION! |

|

|