JOHN WILKES BOOTH'S MOVEMENTS ON THE DAY OF THE ASSASSINATION - APRIL 14, 1865 |

|

|

9:00 A.M.

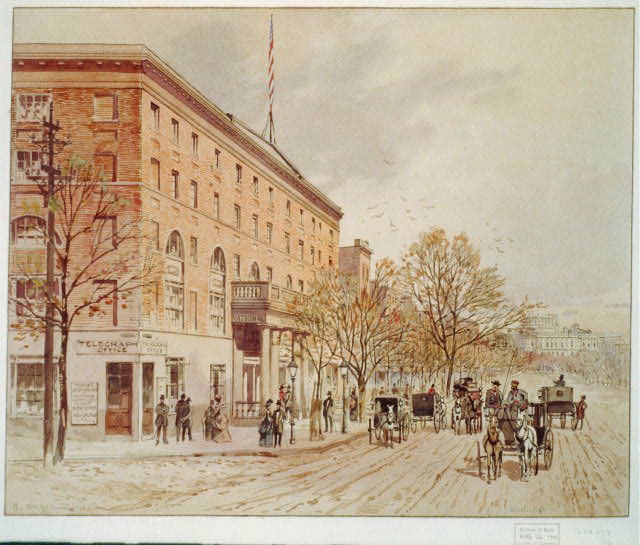

Booth met with his fiancee, Lucy Hale (daughter of John P. Hale, former U.S. Senator from New Hampshire). He then went to Booker and Stewart's barbershop on E Street near Grover's Theatre where barber Charles Wood trimmed his hair. Afterwards, he may have stopped at the Surratt boardinghouse and met with Mary Surratt. Booth then returned to his hotel in Washington. This was the National Hotel, just 6 blocks from the Capitol on the northeast corner of Sixth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. Booth stayed in room 228. Many guests recognized Booth as he walked in because he was one of America's most famous actors. No one noticed any suspicious behavior whatsoever. Booth's friend, Michael O'Laughlen, dropped by for a brief visit.

THE NATIONAL HOTEL (Library of Congress)

|

|

11:00 A.M.

Booth left the National Hotel and went to Ford's Theatre to pick up his mail. He was dressed in dark clothes and wore a tall silk hat. He wore kid gloves of a bland color, had a light overcoat slung over his arm, and carried a cane. At Ford's he learned from Henry Clay Ford, 21, that President Abraham Lincoln would be attending the evening performance of Our American Cousin. Booth then spent some time walking around the theater. He knew nearly every line of the play. He figured out that the greatest laughter in the theater would be taking place about 10:15 P.M. He also realized the actor, Harry Hawk, would be alone on stage at that moment. He made up his mind. This would be the time to assassinate the president.

|

|

12 Noon

Booth showed up at a stable at 224 C Street operated by James W. Pumphrey, 32, and rented a fast roan mare. He said he'd pick the horse up at 4:00 P.M. that afternoon. He then returned to his room at the National Hotel.

|

|

2:00 P.M.

Booth walked to the Herndon House where fellow conspirator Lewis Powell was staying. Booth told Powell of the night's plans. Booth's plan for Powell was to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward. He told Powell it was time to check out of the Herndon House. At about 2:30 he dropped by the Surratt boardinghouse. He gave Mary Surratt a package containing field glasses and apparently asked her to take them to her leased tavern in Surrattsville. (Booth picked these up from John Lloyd at the tavern at around midnight.)

Lloyd later testified she told him to ready the weapons hidden at the tavern. Lloyd maintained Mary "told me to have those shooting-irons ready that night, there would be some parties who would call for them.”

|

|

3:00 P.M.

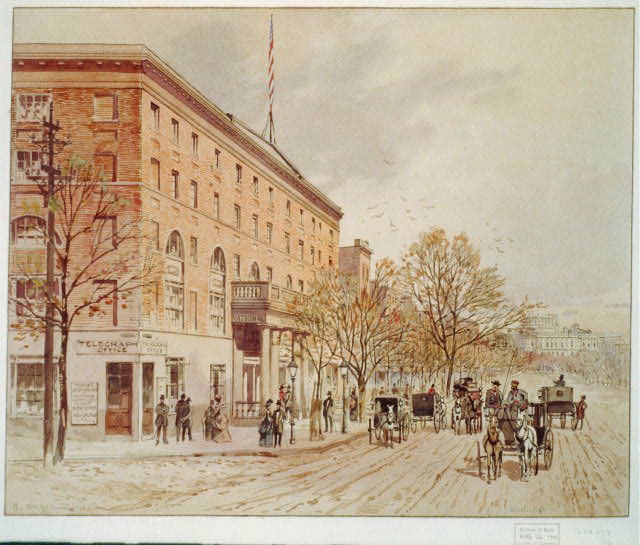

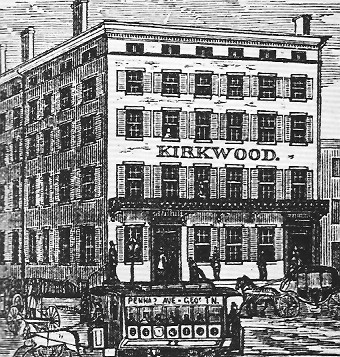

Booth went to the Kirkwood House to discuss plans with fellow conspirator George Atzerodt. Booth wanted Atzerodt to assassinate Vice-President Andrew Johnson who lived at the Kirkwood House. Atzerodt was out. Booth left a note for the vice-president (or his personal secretary) with Robert Jones, the desk clerk. ** Historians have differing interpretations of why Booth left a message for Johnson or his secretary; no one really knows for sure why he did it. The note said, "I don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth." Johnson was not in; rather he was at the White House.

SKETCH OF THE KIRKWOOD HOUSE (National Park Service)

|

|

4:00 P.M.

Booth picked up the mare he'd rented at Pumphrey's Stable. He stopped at Grover's Theatre and went upstairs to Deery's tavern for a drink. He then went downstairs and wrote a letter. It was written to the editor of a Washington D.C. newspaper called the National Intelligencer. He explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating him. He signed the letter not only with his own name but also three of his co-conspirators: Powell, Atzerodt, and Herold. Then he got up and went back outside to his horse. |

|

5:00 P.M.

Booth walked his horse down Fourteenth Street. Near Willard's Hotel he met a fellow actor named John Mathews. Mathews was playing the role of Richard Coyle in Our American Cousin. He gave Mathews the letter and asked him to deliver it to the National Intelligencer the next day. Booth got on his horse and rode off. He passed by Ulysses S. Grant's carriage. On a side street he met up with George Atzerodt. He told a reluctant Atzerodt to kill Andrew Johnson as close to 10:15 as possible. |

|

6:00 P.M.

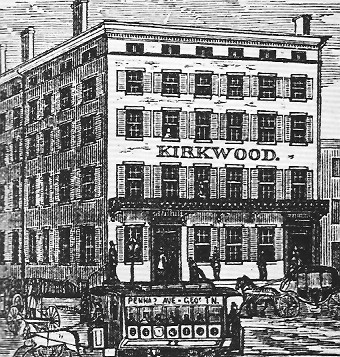

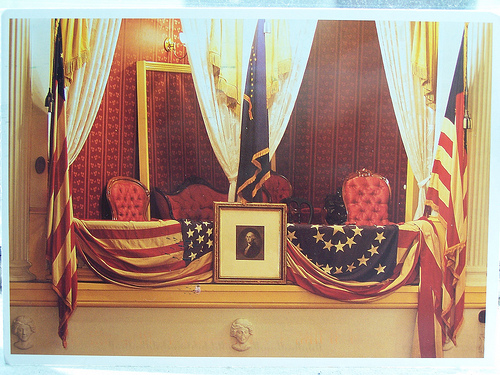

Booth rode to Ford's Theatre. He invited several Ford's employees, including Ned Spangler, out for a drink at Taltavul's Star Saloon. Afterwards, he returned to the theater and traveled the route he would use in the assassination. He practiced everything except the leap to the stage. Using a gimlet, he even drilled a small hole in the door in back of where Lincoln would be sitting which would give him a decent view of where Lincoln's head and shoulders would be. (This is disputed by at least one member of the Ford family; see pp. 73-75 of W. Emerson Reck's A. Lincoln: His Last 24 Hours.) Then he went out the back of the theater and returned to the National Hotel to rest and have dinner.

THE STATE BOX IN FORD'S THEATRE

|

|

7:00 P.M.

Booth put on black riding boots, new spurs, a black frock coat, black pants, and a black slouch hat. He picked up his diary. Booth carried a compass, a small derringer, and a long hunting knife that could be stuck inside his pants on the left side. Booth loaded the .44-caliber derringer with a lead ball. It was a single shot pistol. At 7:45 he exited the National Hotel.

|

|

8:00 P.M.

Booth held one final meeting with his co-conspirators (both the time and location of this meeting is not known for certain). Powell would assassinate Secretary Seward. Herold would guide Powell to Seward's home and help him escape from Washington. (Historians debate whether or not Herold was with Powell at Seward's home.) Atzerodt would shoot Vice-President Johnson. Booth would kill Lincoln. All attacks would take place simultaneously at 10:15 P.M. The entire gang would then meet at the Navy Yard Bridge. From there they would ride to Surrattsville and pick up guns and binoculars at John Lloyd's leased tavern.

|

|

9:00 P.M.

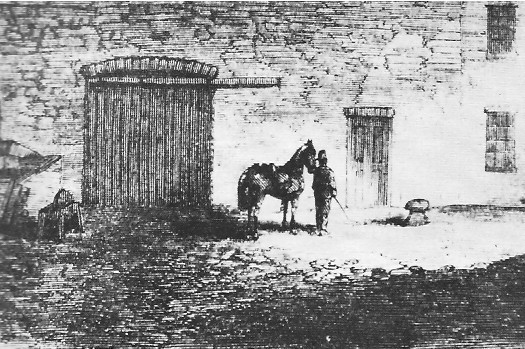

Booth arrived at Ford's Theatre in the vicinity of 9:30. He called Ned Spangler to hold his horse in the alley in back of Ford's. Spangler was busy changing sets for the play and asked another employee, a lad named Joseph C. Burroughs, to take care of the mare. Booth went to Taltavul's Star Saloon next to the theater and requested a bottle of whiskey and some water. Another customer said to Booth, "You'll never be the actor your father was." Booth replied, "When I leave the stage, I will be the most famous man in America." (Booth's statement is probably apocryphal.)

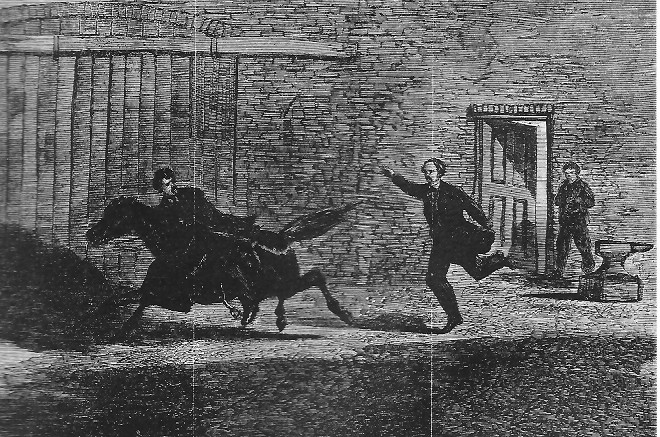

JOSEPH BURROUGHS, NICKNAMED PEANUT JOHN, HELD BOOTH'S HORSE

Sketch from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 13, 1865

|

|

10:00 P.M.

Booth entered Ford's lobby at about 10:07 P.M. He went up the stairs to the dress circle. He moved slowly even stopping completely to lean back against the wall. Soon Booth could see the white door he needed to enter to get to Lincoln's State Box. Charles Forbes, the president's footman, was seated next to the door and Booth apparently handed him a card. Quietly, Booth then opened the door and entered the dark area in back of the box. It was now between 10:15 P.M. and 10:30 P.M. Booth propped the door shut with the wooden leg of a music stand which he had placed there on one of his earlier visits during the day. Whether Booth actually made the niche in the wall was disputed by at least one member of the Ford family; see pp. 73-75 of W. Emerson Reck's A. Lincoln: His Last 24 Hours.

|

He then opened an inside door behind where the president was sitting. He put his derringer behind Lincoln's head near the left ear and pulled the trigger. Because of the laughter in the theater, not all patrons heard the shot. Booth may have said, "Sic semper tyrannis!" (Latin for "Thus always to tyrants"; many in the audience thought he said these words after he landed on the stage; not all eyewitnesses agreed on Booth's words or even if there were any.) Major Henry Rathbone, also sitting in the State Box, thought Booth shouted a word that sounded like "Freedom!" Rathbone began wrestling with the assassin, and Booth pulled out his knife and stabbed Rathbone in the left arm.

CLICK HERE TO SEE BOOTH'S WEAPONS |

|

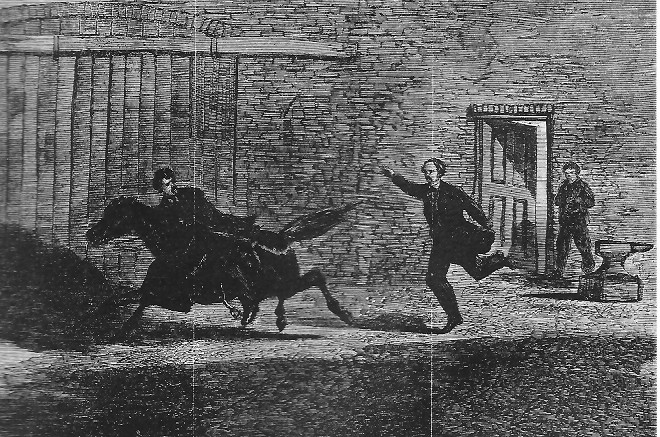

Booth climbed over the banister of the box and dropped about 11 feet to the stage. He landed off balance snapping the fibula bone in his left leg just above the ankle. (At least one assassination expert, Michael Kauffman, feels Booth did not break his leg in his leap to the stage. Kauffman feels Booth broke his leg later that night when his horse took a fall.) Adrenalin flowing, Booth flashed his knife and quickly crossed the stage and out the back of the theater. He jumped on his mare and escaped from the area. At approximately 10:45 Booth crossed the Navy Yard Bridge. Soon he would be in Maryland.

Sketch from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 13, 1865

THE NAVY YARD BRIDGE USED BY BOOTH AND HEROLD TO ESCAPE

National Archives and Records Administration, Photo by Mathew Brady's studio

|

|

11:00 P.M.

David Herold, who used the same bridge to escape from Washington, caught up with Booth probably near Soper's Hill. The two then rode together headed for Lloyd's tavern that was leased from Mary Surratt in Surrattsville (name changed first to Robeystown on May 3, 1865, and finally to Clinton on October 10, 1878).

|

|

12 Midnight

|

|

More than 11 miles south of Ford's Theatre, Booth and Herold arrived at Mary Surratt's tavern. Booth had a drink of whiskey, and the fugitives picked up field glasses and a Spencer rifle. John Lloyd later testified that Booth said, "I am pretty certain that we have assassinated the President and Secretary Seward." At the time Booth didn't know Powell failed to kill Seward, and Atzerodt had made no attempt to kill Johnson. Because his leg was hurting terribly, Booth needed medical attention. The whiskey provided only temporary relief. Booth and Herold rode off into the dark countryside. They rode through T.B. and past the home of Joseph Eli Huntt. They eventually ended up at Dr. Samuel Mudd's house at approximately 4:00 A.M.

STREET IN SURRATTSVILLE - Looking north from the front of the Surratt house toward Washington; the road by which Booth and Herold entered the town. Source: p. 244 of The Assassination of

Abraham Lincoln by Osborn H. Oldroyd.

|

|

|

WORST SEAT IN THE HOUSE

Caleb Stephens' Worst Seat in the House is the first non-fiction book to examine Henry Rathbone's life and how the Lincoln assassination affected him. Rathbone was the only person to confront assassin John Wilkes Booth. Henry struggled with the killer, but ultimately lost after Booth slashed him with a dagger.

Eighteen years later, Henry murdered his wife, Clara, by shooting her and stabbing her on Christmas Eve. He then turned the knife and stabbed himself five times.

He spent the last twenty eight years of his life in an insane asylum in Germany.

To order Caleb Stephens' book please CLICK HERE.

|

|

|

** In the 1997 publication "Right or Wrong, God Judge Me": The Writings of John Wilkes Booth edited by John Rhodehamel and Louise Taper it is stated on p. 146 that Booth had previously met Johnson in Nashville in February, 1864. At the time Booth was appearing in the newly opened Wood's Theatre. Also, Hamilton Howard in Civil War Echoes (1907) made the claim that while Johnson was military governor of Tennessee, he and Booth kept a couple of sisters as mistresses and oftentimes were seen in each other's company. |

|

A new hardback edition of Clara E. Laughlin's The Death of Lincoln: The Story of Booth's Plot, His Deed, and the Penalty has been published. Laughlin's book was originally published on February 9, 1909, the centennial of Lincoln's birth. The new edition contains an index and a preface by Lincoln assassination scholar and author, Michael W. Kauffman. If you would like to obtain a copy, contact Tony O'Connor's Vt. Civil War Enterprises at (802) 766-4747 or send e-mail to vtcwe@hotmail.com.

Although the information contained on this page was gathered using many sources (see the bibliography here), I have used Jim Bishop's The Day Lincoln Was Shot for the page's basic outline.

Thank you to James Warner for contributing the "composite" at the top of the page.

|