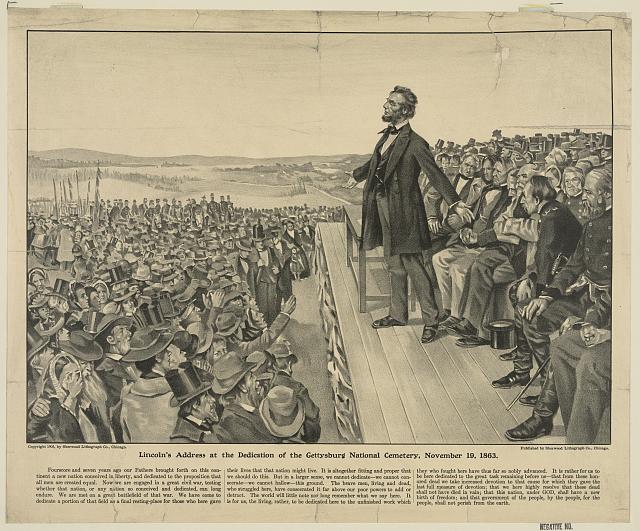

Lincoln's main goals were to dedicate the battlefield to the men who died there and to explain to the nation why the Civil War was worth fighting and would continue to be fought.

He referred to the past when he said, "Four

score and

seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation,

conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are

created equal." This was a reference to the Founding Fathers who had

adopted the Declaration of Independence which outlined the reasons the

colonists were breaking away from England.

He referred to the present when he said, "Now we are engaged in a great

civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so

dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war.

We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place

for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is

altogether fitting and proper that we should do this." This meant that our

nation was fighting a great Civil War to see if we would survive as a

country. He thought it was a proper thing to dedicate a portion of the

Gettysburg battlefield as a remembrance of the men who had fought and died

there.

He referred to the future when he said, "It is for us the living, rather, to

be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have

thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the

great task remaining before us -- that from these honored dead we take

increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure

of devotion -- that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have

died in vain -- that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of

freedom -- and that government of the people, by the people, for the people,

shall not perish from the earth." Lincoln was saying that the people who

were still alive must dedicate themselves to finish the task that the dead

soldiers had begun which was to save the nation so it would not perish from

the earth. Lincoln felt that the Southern states could not legally leave

the Union and form their own country, and that the North was going to continue

to use force to bring the South back into the country.

After the speech Lincoln had an unplanned, handshaking reception at the Wills' home. This went on for about an hour. He also visited Gettysburg's Presbyterian Church.

That evening the special train departed Gettysburg about 7 P.M., and it arrived back in Washington at about 1:10 A.M. on Friday, November 20. The president was actually in Gettysburg proper for about 26 hours. On the train home he was quite weary.

He talked little, stretched out on one of the side seats in the drawing room and had a wet towel placed across his eyes and forehead. Within a week of his return he was quite ill with varioloid, a mild form of smallpox. Lincoln remained under quarantine for about three weeks. During this period of illness (late 1863) he saw few visitors and transacted little business.

Notable attendees at Gettysburg included the following people: Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania,

Governor Augustus W. Bradford of Maryland, Governor Oliver P. Morton of Indiana, Governor Horatio Seymour

of New York, Governor Joel Parker of New Jersey, Governor William Dennison, Jr. of Ohio,

ex-Governor David Tod and Governor-Elect John Brough of Ohio, speaker Edward Everett

and his daughter, Ward Hill Lamon, Secretary of State William Seward, Postmaster

General Montgomery Blair, Chaplain of the United States House of Representatives

Thomas H. Stockton, Benjamin B. French (who was the officer in charge of buildings in

Washington) and many others.

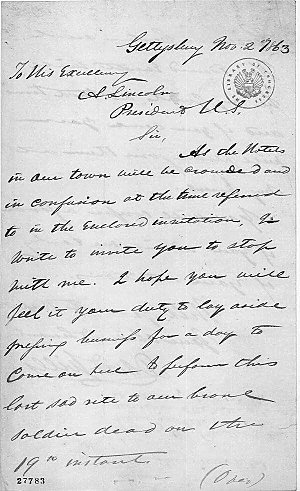

There are various myths on how Lincoln actually wrote the address. There is

the legend

that he wrote it on the back of an envelope. Another legend has him writing

it on a piece of cardboard as the train traveled its 80-mile trip from

Washington to Gettysburg. Still another story has him writing it at his

host's house the night before giving the address

itself. However, all of these legends are out of character for

Lincoln. He took the occasion very seriously. The most reliable accounts

of the

speech's origin are that he essentially composed it in Washington and

perhaps made a few refinements while staying overnight at David Wills'

house. Two of Lincoln's friends...Noah Brooks and Ward Hill Lamon...

said that Lincoln wrote the speech in the White House prior to leaving

for Gettysburg.

Lincoln wrote five different versions of his speech. He wrote

most of the

first version in Washington, D.C., and probably completed it at Gettysburg.

He probably wrote the second version at Gettysburg on the evening before he

delivered his address. He held this second version in his hand during the

address. But he made several changes as he spoke. The most important

change was to add the phrase "under God" after the word "nation" in the last

sentence. Lincoln also added that phrase to the three versions of the

address that he wrote after the ceremonies at Gettysburg.

Lincoln wrote the final version of the address...the fifth written

version...in 1864. This version also differed somewhat from the speech he

actually gave, but it was the only copy he signed. It is carved on a stone

plaque in the Lincoln Memorial. Two copies of the Gettysburg Address are in the

Library of Congress, one is in the Lincoln Bedroom of the White House, one is

in the Cornell University Library, and one is in the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.

On the platform after the speech, Lincoln allegedly remarked to Ward Hill Lamon, "Lamon, that speech won't scour! It is a flat failure and the people are disappointed."

The Gettysburg Address didn't earn lasting

fame until after Lincoln's death; initial reaction was mixed. Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow told the editor of

Harpers Weekly that he found the

address "admirable."

Harpers called the address as "simple and felicitous

and earnest a word as ever was spoken." Josiah Gilbert Holland of the

Springfield, Massachusetts

Republican called the speech "a perfect gem"

and said "the rhetorical honors of the occasion were won by President

Lincoln." The

Chicago Tribune announced that "The dedicatory remarks by

President Lincoln will live among the annals of man." John W. Forney,

writing in the

Washington Chronicle, said that the address "though short,

glittered with gems, evincing the gentleness and goodness of heart peculiar

to him." The

Providence Journal said, "We know not where to look for a

more admirable speech than the brief one which the President made."

On a more negative note, the

New York World accused Lincoln of "gross

ignorance or willful mis-statement." Wilbur F. Storey of the

Chicago

Times wrote "that invoking the Declaration of Independence Lincoln was

announcing a new objective in the war." Storey continued, calling the

address "a perversion of history so flagrant that the most extended charity

cannot regard it as otherwise than willful."

Abraham Lincoln never knew that his Gettysburg Address would become one of the most famous speeches in American history.

|