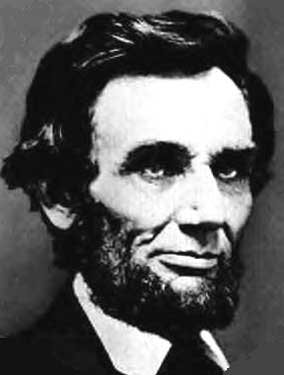

DEPRESSED? READ ABRAHAM LINCOLN'S WORDS

|

Executive Mansion

Washington, December 23, 1862.

Dear Fanny

It is with deep grief that I learn of the death of your kind and brave Father; and, especially, that it is affecting your young heart beyond what is common in such cases. In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and, to the young, it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares. The older have learned to ever expect it. I am anxious to afford some alleviation of your present distress. Perfect relief is not possible, except with time. You can not now realize that you will ever feel better. Is not this so? And yet it is a mistake. You are sure to be happy again. To know this, which is certainly true, will make you some less miserable now. I have had experience enough to know what I say; and you need only to believe it, to feel better at once. The memory of your dear Father, instead of an agony, will yet be a sad sweet feeling in your heart, of a purer and holier sort than you have known before.

Please present my kind regards to your afflicted mother.

Your sincere friend

A. Lincoln |

|

Abraham Lincoln wrote this beautiful letter of condolence to Fanny McCullough, the daughter of William McCullough who was the former clerk of the McClean County Circuit Court in Bloomington, Illinois. William McCullough knew Abraham Lincoln well. Fanny could remember when she was a child Lincoln would hold her and her sister Nanny on his knees. During the Civil War McCullough, a Black Hawk War veteran, enlisted in the Fourth Illinois Cavalry, and he was killed in a battle near Coffeeville, Mississippi, on December 5, 1862. Mutual friends of Lincoln and McCullough informed the president of Fanny's depression over her father's death. With the help of Lincoln's letter, Fanny eventually recovered, married, and lived until 1920.

More than 20 years earlier Lincoln gave similar advice to his best friend, Joshua Speed. In a letter written on February 13, 1842, Lincoln said: |

Remember in the depth and even the agony of despondency, that very shortly you are to feel well again. |

|

In a September 27, 1841, letter to Mary Speed, a half sister to Joshua, Lincoln noted: |

A tendency to melancholy.... let it be observed, is a misfortune, not a fault. |

|

Without question Lincoln was subject to periods of melancholy throughout his life. His own term for it was "the hypo" (short for hypochondriasis). Lincoln was probably a believer in the doctrine of fatalism. Additionally, he was somewhat superstitious. However, his ability to cope with whatever depression afflicted him, especially late in life, was enormous. Using various means... work, humor, fatalistic resignation, or even religious feelings... he generally did not allow the depression or melancholy to interfere with his work as president. He overcame this depressive aspect of his personality with a powerful inner strength and will.

Although most of Abraham Lincoln's written references to depression were in a series of 1841-1842 letters to Joshua Speed, Lincoln's most profound quote on his own personal depression comes from another source. On January 1, 1841, Lincoln broke up with Mary Todd (the woman he would marry in November of 1842). Afterwards, later in January of 1841, he entered a period of depression. He was absent from the Illinois state legislature from January 13th to 19th due to illness which was most likely due to some sort of melancholy (which most likely was due to his ending his relationship with Mary). On January 23, 1841, Lincoln wrote a letter to John T. Stuart, his first law partner. In the letter, Lincoln stated: |

|

|

I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth. Whether I shall ever be better I can not tell; I awfully forebode I shall not. To remain as I am is impossible; I must die or be better, it appears to me. |

|

|

People who knew Lincoln noticed his gloominess. William Herndon, Lincoln's third law partner, described Lincoln as follows: "He was not a pretty man by any means, nor was he an ugly one; he was a homely man, careless of his looks, plain-looking and plain-acting. He had no pomp, display, or dignity, so-called. He appeared simple in his carriage and bearing. He was a sad-looking man; his melancholy dripped from him as he walked. His apparent gloom impressed his friends, and created sympathy for him - one means of his great success. He was gloomy, abstracted, and joyous - rather humorous - by turns; but I do not think he knew what real joy was for many years... The perpetual look of sadness was his most prominent feature."

Francis B. Carpenter, an artist who lived in the White House for part of 1864, said of Lincoln, "I have said repeatedly to friends that Mr. Lincoln had the saddest face I ever attempted to paint." Joshua Speed said of his first meeting Lincoln, "As I looked up at him I thought then, and think now, that I never saw a sadder face." Fellow lawyer, Henry C. Whitney, who traveled across the legal circuit in Illinois with Lincoln, thought "no element of Mr. Lincoln's character was so marked, obvious, and ingrained as his mysterious and profound melancholy." Even as a boy growing up in Indiana, friend James Grigsby said Lincoln would "get fits of blues, then he wouldn't study for two or three days at a time."

Robert L. Wilson served in the Illinois legislature with Lincoln. Regarding Lincoln's gloominess, Wilson wrote: |

|

In a conversation with him about that time (1836), he told me that although he appeared to enjoy life rapturously, still he was the victim of terrible melancholy. He sought company, and indulged in fun and hilarity without restraint, or stint as to time. Still when by himself, he told me that he was so overcome with mental depression, that he never dare carry a knife in his pocket. As long as I was intimately acquainted with him, previous to the commencement of the practice of the law, he never carried a pocketknife, still he was not a misanthropic. He was kind and tender in his treatment to others. |

|

Those around him noticed that Lincoln could go from a happy state to a gloomy one very quickly. Fellow attorney Jonathan Birch said of Lincoln in court, "His eyes would sparkle with fun, and when he had reached the point in his narrative which invariably evoked the laughter of the crowd, nobody's enjoyment was greater than his. An hour later he might be seen in the same place or in some law office near by, but, alas, how different! His chair, no longer in the center of the room, would be leaning back against the wall; his feet drawn up and resting on the front rounds so that his knees and chair were about on a level; his hat tipped slightly forward as if to shield his face; his eyes no longer sparkling with fun or merriment, but sad and downcast and his hands clasped around his knees. There, drawn up within himself as it were, he would sit, the very picture of dejection and gloom. Thus absorbed have I seen him sit for hours at a time defying the interruption of even his closest friends. No one ever thought of breaking the spell by speech; for by his moody silence and abstraction he had thrown about him a barrier so dense and impenetrable no one dared to break through. It was a strange picture and one I have never forgotten."

What were the roots of Lincoln's depression? A definitive answer is impossible. It could have been heredity. Whitney said, "His melancholy was stamped on him while in the period of gestation. It was part of his nature." Some of Lincoln's cousins may have suffered from depression, and there are indications his parents suffered from bouts with the blues. Others feel a lonely and depressive youth contributed to his later melancholy. Growing up on the frontier young Lincoln was unique in his interests in politics, reading, etc., and his intellectual power partially isolated him from his peers. Additionally, he suffered through the deaths of his younger brother, mother, and older sister. A few have speculated that his depression was rooted in his lowly upbringing and feelings of insecurity when he was around people from a richer social order. Herndon felt Lincoln's depression might have dated to Thomas Lincoln's cold treatment of his son. Father and son were indeed estranged. Abraham did not visit Thomas when he was informed his father was dying. He did not attend Thomas' funeral in 1851. Thomas Lincoln died never having met Mary Todd Lincoln, seen his grandchildren, or even visited Springfield where his son's family lived.

Not only did Abraham Lincoln suffer from serious bouts of depression, but he also tried to give advice to others he knew were suffering. Lincoln's depressions, whether they lasted for hours, days, weeks, or months always came to an end. Knowing this, he could encourage others. It would seem his own experience led him to believe that depression was not a permanent condition. |

|

For additional information on Abraham Lincoln and depression, two recent books attempt to create a psychological profile of the 16th president. They are (1) The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln by Michael Burlingame and (2) Honor's Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln by Douglas L. Wilson. Chapter 5 entitled "Lincoln's Depressions: Melancholy Dript From Him As He Walked" in Burlingame's book is an especially well documented source of information. Additionally, Lincoln's law partner, William Herndon, gives a first hand account of Lincoln's melancholy in his biography of Lincoln entitled Herndon's Life of Lincoln. Also, Mark E. Neely, Jr., author of The Abraham Lincoln Encyclopedia discusses Lincoln's depression within the topic 'Psychology.'

There are indications Lincoln took a medication for his hypochondriasis called blue mass. This was a commonly prescribed medication in the 19th century for ailments such as apoplexy, worms, tuberculosis, toothaches, constipation, and hypochondriasis. Blue mass contained mercury and can lead to the neurobehavioral consequences of mercury poisoning. John Stuart said that Lincoln took blue mass "before he went to Washington and for five months while he was President." For details on this possibility in Lincoln's life, please see "Abraham Lincoln's Blue Pills: Did Our 16th President Suffer From Mercury Poisoning?" by Norbert Hirschhorn, Robert G. Feldman, and Ian A. Greaves in Perspectives in Biology and Medicine Volume 44, Number 3 (summer 2001), pp. 315-332 2001 by the Johns Hopkins University Press.

Book-length treatment of Lincoln and depression was published in 2005. The book is called Lincoln's Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness by Joshua Wolf Shenk (Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005).

|

|